By Wendy Williams

As the taciturn waiter served up an industrial strength coffee, I gently probed as to where I might find the local mayor to seek out an interview.

He looked at his watch and, almost cracking a smile, replied: “At this time? He’ll still be asleep.”

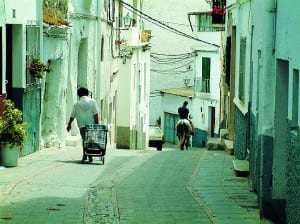

It was actually already 9:45am in the heart of July, yet in Capileira most of the locals were still sleeping and only one of the dozen or so cafe/bars was actually open for business.

Strange for such an emblematic village – Spain’s second-highest – and a regular stopping off point for tourists and hikers from around the world.

Life certainly starts later in the Alpujarras and the pace of life is slower than the majority of its waiters.

But this, of course, gives you all the more chance to absorb the beautiful scenery.

And there is certainly no shortage of that in this charming region, made famous first by British writer Gerald Brenan in his book South from Granada, and more recently by Chris Stewart, of Driving over Lemons fame.

La Alpujarra (or Las Alpujarras depending on who you ask – even the road signs can’t make up their minds) is a landlocked mountainous region which stretches south from the Sierra Nevada mountain range, around 40 to 50kms inland from the coast.

A colourful region of legends (and perhaps even more colourful people), it is one of the driest spots in Spain although this is anything but obvious, its terraced farmlands well watered by melting snow carefully channelled into water courses.

It is this series of acequias – first installed by the ancient Moors – that have helped to make the upper valleys an oasis of green, in dramatic contrast to the arid foothills on the facing slopes of the Contraviesa nearer the coast.

On first glance, the region is a pastoral paradise, its 50-odd villages apparently alive from farming and a generous smattering of tourists.

Decidedly rural and great for a holiday, these villages (along with those in the nearby Lecrin Valley) were also as it happens the last stronghold of the Moors.

This apparently sleepy enclave has a very bloody history due to the Reconquest

Indeed, this apparently sleepy enclave has a very bloody history, following the Reconquest of Granada in 1492, in which the muslim Moors were forced to convert to Christianity.

Those who refused took to the hills, settling in this remote area where they were able to maintain a distinct culture for decades.

But the peace wasn’t to last and in 1568 there was a bloody uprising – the Morisco Rebellion – which was ruthlessly crushed leading to their eviction from the area, with the exception of two Moorish families for each village.

Legend has it; these families were ordered to remain by the Spanish crown to maintain the complicated irrigation systems.

Certainly, the unique villages have retained much of their traditional Berber-style architecture with terraced clusters of white houses with flat clay roofs and chimneys, which are unique to the region.

And the locals don’t seem to be losing sleep over their violent past.

In fact, they are getting plenty of it… certainly if being a mayor is anything to go by.

For the following day we were to be confronted by yet another sleeping mayor after my colleague left his camera in another town hall which by the time we returned was typically shut for the day.

Told that nobody would be back until the next day, we eventually tracked down the mayor, who conveniently owned the local supermarket.

The only problem… he was already taking his daily siesta and couldn’t be disturbed. But then his wife, who was cutting ham on the deli counter, promptly came up with a solution and without comment, simply handed over the keys to the town hall.

Now, I don’t know if this is common practice but it showed a level of trust scarcely seen where I grew up and where I currently live in Malaga.

It also added to a growing impression that the people of the Alpujarras belong to a different time, largely untouched by the modern world.

The whole feel of the region is distinctly rough and ready, unpolished and parochial, yet with none of the pretensions you find on the coast.

Further proof of this came in the evening when, while enjoying tapas in a leafy square, the waitress asked if she and her husband could lock up and we simply leave our glasses and plates behind a plant pot.

“It is certainly a timeless place” explained Chris Mann, 52, who splits his time between Brighton and the village of Cañar.

“We absolutely love the Alpujarras because it is still distinctly the real Spain.

“There are no English breakfasts and no fish and chips… and I don’t think they’ll ever change that.”

He added: “The Spanish here are very hardworking, strong mountain people.”

“But,” he quipped, “it takes six months for your neighbour to first say hello.”

This is certainly the case, with locals showing a distinct wariness as we went about seeking information, photos and anecdotes.

Reticent to open up and some openly hostile, it is largely thanks to the large influx of Spaniards from the north and the rich mix of expatriates, that the region keeps its balance.

Plus there is another dimension to the Alpujarras with the two biggest towns Lanjaron and Orgiva, offering an entirely different flavour to the mountain villages.

Lanjaron is famous around Spain for its waters… and rather like Bournemouth, is full of old folk who flock to the area for its apparent healing properties.

In a scene more reminiscent of a Roman hospital than a relaxing retreat, as you enter the Balneario you are greeted by a gaggle of pensioners lining up with their plastic cups to drink the famous water.

But there are also plenty of other things going on around Lanjaron.

First and foremost, with its enviable location at the gateway to the Alpujarras, it is an ideal base for walkers and climbers.

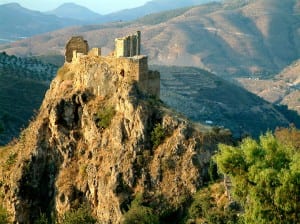

Moreover, visible from the town are the impressive ruins of a Moorish castle which stands precipitously above a ravine.

According to legend when the castle was stormed by the Christians some of the Moors actually threw themselves off the edge.

Lanjaron also boasts a number of craft shops selling wickerwork for which the town is well-known.

This all stands in contrast to nearby Orgiva which is the veritable new age capital of Spain with three camps for travellers located just outside the town.

Here you are more likely to find people with dreadlocks and dogs on strings than grandpas in socks and sandals.

While the famous ‘flute woman’ has apparently now disappeared from the steps of the Iglesia de Nuestra Senora de la Expiracion – the impressive church that dominates the skyline – there are plenty of other colourful people to make up for it.

In fact I was lucky enough to come across ‘the cigarette man’ not once but twice, in two different towns. A slightly dishevelled looking figure, he gruffly asks for cigarettes before snatching one and disappearing without so much as a thank you.

“He’s infamous and weirdly no one has ever seen him smoking,” explained one local expat.

Of course Orgiva seems positively bustling in contrast to the nearby villages.

Car horns were beeping as a traffic jam along the main road seemed to bring the town to a standstill.

But in truth, Orgiva is also incredibly laid back, with rumours there are lay lines that run through the town.

There is certainly an indefinable quality felt by the hundreds of expats, who have been drawn to the town like magnets.

“There are a lot of different people here – Muslims, Buddhists, hippies – many of whom have travelled a lot and then stayed,” explains Qasim Barrio, 38, who runs the restaurant Baraka.

“Orgiva might not have that much or be the most beautiful place but people can come here and live how they like without being judged or being afraid, it offers the possibility to be themselves.”

This is a view also supported by writer Bill Crossick, 45, originally from Yorkshire, who settled here after travelling for 23 years.

“I went through Israel and Eastern Europe. But I was limited by my fear of flying so I had to drive everywhere or go by bus, train or hitchhike,” he explained.

“Then I arrived in Orgiva 10 years ago as a volunteer on an organic farm, I did a few months and went home and then came back. I bought a truck and converted it as a way of staying permanently, before eventually buying land below Cañar where I built a house.”

Crossick, who has written two anthologies of poems and short stories about his experiences added: “The area reminds me a lot of the Middle East, it is very similar in many ways and I have very happy memories of it so I stayed here.

“Plus it is the only place where I could manage to sustain myself, live cheaply and buy land.

“In the beginning I was actually selling books on the church steps to get some money together.

“I couldn’t have done that anywhere else.”

Quite simply, the Alpujarras is like nowhere else on earth.

From the time of the Moors to the modern day it has provided a refuge for those that were running away or who just wanted to be free to live in their own way.

Ultimately it is a magical place full of contrasts; it boasts lush greenery next to arid landscapes, it is one of the driest places in Spain, yet famous for its water, it is a timeless zone, yet modern in thinking, and it offers ‘real’ Spain, while attracting interesting people from all around the world.

And to top it all off, sometimes you really do drive over lemons to get there.

I don’t know whether to be glad about articles such as this, which keep the Alpujarra (singular, please!) on the map and safe from becoming depopulated, or sad. The tourist ‘carrot’ is gradually turning the Alpujarra alta (the Barranco de Poqueira area) into an ad hoc museum, whereas the Alpujarra baja, closer to the Almeria end, manfully, and in some cases slightly pathetically makes a huge effort to attract tourists.

Like most people find as they grow older, when I return to the Alpujarra baja on infrequent visits, I tend to see what is no longer there: the trees that have been cut, the springs that have dried up, the land left fallow, and the people whose ghosts smile at me from the street corners.

Thanks all the same, Wendy. Your article is sensitive, well written and informative. The Alpujarra deserves people like you.