THE expression ‘cloak and dagger’ is one which invokes dynamic images of James Bond-like stealth, danger and espionage.

Linguists tell us that the phrase is actually Spanish in origin – literally, ‘capa y espada’ – and the term can be traced to Andalucia.

The phrase developed from martial arts techniques popular throughout Andalucia during the 17th and 18th centuries.

In Sevilla, Cordoba and especially Malaga, sophisticated dagger-fighting schools evolved from the more traditional fencing and sword academies.

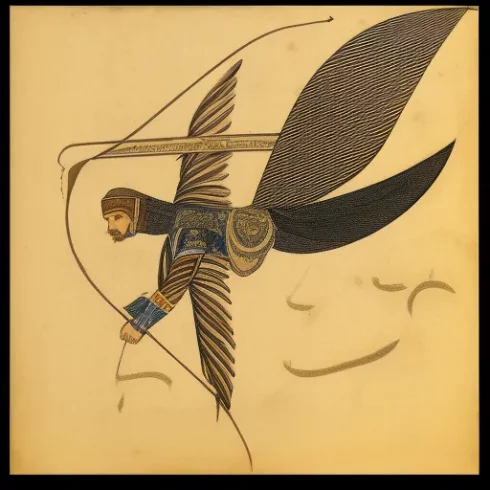

The new focus was in skills of deception, distraction and counter-strike using a dagger and a cloak worn to supplement fighting techniques.

The cloak was typically a three-quarter circle of cloth, custom-fitted to the height of the wearer.

It enabled a man to hold his dagger out of sight and simultaneously block an incoming attack by wrapping the cloak around his opponent.

Cloaks were worn with a long, elongated hat drawn down over the ears to conceal eye movements.

Cloak and dagger, the uniform of these Andalucian schools, would go on to be iconic symbol in Spanish history.

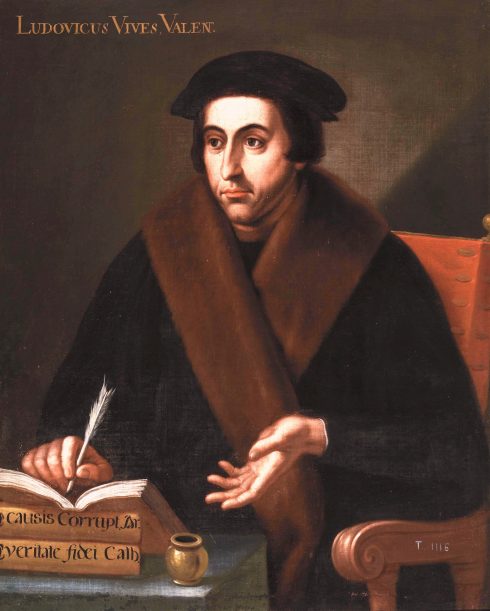

Cloaks of similar style were the fashion rage in 18th-century Spain. They were worn by soldiers, aristocrats, the bourgeois, clergymen and, unsurprisingly, by criminals. Rising prices and taxes on bread, coal, oil, wine and cured meats fanned widespread discontent. Petty crime, robberies and muggings were commonplace as social tensions ran high, to the extent that Charles III banned cloaks in an attempt to tighten public security.

Publicly, Charles stated that he sought to substitute the long capes and broad-brimmed hats with short capes and three-cornered hats worn by the French as a way of ‘modernising’ Spain. Privately, however, Charles sought to curb street-crime, believing that the long capes facilitated the concealment of weapons while the elongated hats hid faces.

The public reaction to the ban was swift and violent.

Protesters marched on Plaza Mayor, official palaces were looted and governmental authorities were stoned and knifed.

Soldiers were mobilised but rioters promptly took control of a military arsenal where muskets and sabers were stored.

Charles was forced to flee Madrid.

The situation reached near-anarchy and it took a military junta to restore order.

The infamous Spanish painter Francisco Goya, an eyewitness to this virtual insurrection of the populace, went on to paint his famous Motin de Esquilache depicting what has become known as the ‘Hat and Cloak Riots’ (a.k.a the Esquilache Riots).

This is not the first time a garment’s intrusion into politics has been less than seamless. More recently, British Prime Ministers Tony Blair and David Cameron have both made public speeches suggesting that the hooded sweatshirt or ‘hoodie’ was worn for trouble-making and antisocial behaviour among teens. As a result, they were banned from several British shopping malls, including Bluewater in Kent.

The hoodie also became an icon in American hip-hop culture following the fatal shooting of teenager Trayvon Martin. A ‘million hoodie march’ was held in racial solidarity, with the garment highlighted as ‘the symbol of injustice’.

Fashion and politics have had a rich, symbiotic history. Clothing has always been a medium for cultural change and social expression and certain garments, like the burka and the bikini, have the ability to take on a wider political significance.

But from the cloak and dagger legacy of Andalucia came a fashion statement that, for a brief period in the late 1700’s Spain, threatened to overthrow a king.

Thank you for that fascinating historical perspective Jack. Can we have more like this? Peter (Houston, Texas)

And Spanish street-fighters still prefer daggers to fists.