MIGUEL meets me by the church. His smile erupts like the sun emerging from behind a cloud. He is 70 years old, has 3 daughters and cares for his capital and its future with all the passion of a latter day King Lear. His greetings are formulaic, inquiring about my family, repeating my answers in the familiar muffled tones of the village dialect, a primordial broth of syllables which challenge both my concentration and comprehension.

MIGUEL meets me by the church. His smile erupts like the sun emerging from behind a cloud. He is 70 years old, has 3 daughters and cares for his capital and its future with all the passion of a latter day King Lear. His greetings are formulaic, inquiring about my family, repeating my answers in the familiar muffled tones of the village dialect, a primordial broth of syllables which challenge both my concentration and comprehension.

We have been friends since I first came to the village over 10 years ago and in that time I have seen how Miguel has aged: the slow shuffling gait, the stooped shoulders and parchment skin, the spreading paunch and the lines written on his face like hieroglyphs, the thinning hair and swollen wrists. I will talk again of Miguel, waking at dawn, 15 years of age long before the plastic invernaderos erupted like sores on the face of the surrounding campo, to harness his mules to the hand held plough and confront the challenge of the sloping shale of the timeless land.

But now he invites me in and we sit in the familiar kitchen. Soon the costa wine glugs into the comfortable glass which resembles the bottom half of a Russian doll buried in the soft paw of this gentle old friend and it is not long before he brandishes the double sided blade and approaches the squatting ham with the refined movement of a determined toreador. Good wine, eh? He mumbles, his face emitting sunshine once again and I know he is about to reminisce about our visit to the Contraviesa in search of vino costa.

We had set off early from the church square, the towering bulk of Arcangel San Miguel ineffective in sheltering us from the stinging blustery wind. Edging carefully along the narrow Calle Iglesia, we pushed forwards beyond the “Old Men’s Bar” negotiating the difficult angle of the junction then out to the valley’s edge to start our winding descent to Castell de Ferro and the inky sea slobbering in the bay.

Miguel squats comfortably in the passenger seat ordering a halt, our first of many, at a roadside invernadero, one of the expansive plastic greenhouses which populate the valley, source of out of season produce for the hungry tables of Northern Europe. Within five minutes he emerges clutching something jealously to his podgy frame. I realise it’s a bundle of cucumbers, held with all the care and pride of a new bride clasping a wedding bouquet. However, there is no ceremony to the sprawling green objects thrust into the back seat as I’m ordered to continue the journey. “A friend of mine, cucumbers” explains Miguel redundantly, squirming about in his seat to regain a comfortable posture.

Leaving Castell behind, we follow the enticing contours of the coast road pursuing our mission past the unsuspecting settlements hugging the coast at regular intervals: Castillo de Banos, La Rábita, Los Yesos, La Mamola finally turning off to make the forbidding ascent to the elevated village of Polopos, perched precariously above the receding sea.

“This was just a mule track,” Miguel informs me as we pass the naked shells of an abandoned building project near La Guapa. Now the road rises before us, a slick tarmac surface until it degenerates higher up the mountain showing evidence of severe weather and regular usage. The deep folds of the surrounding countryside are punctuated with scrub and gorse where no one dare tackle the plunging dark hillsides.

Eventually, however, we approach Polopos teetering ahead of us on the valley edge. The air is much colder here despite the day’s bright sunshine and as we leave the car opposite the picturesque village church, we huddle into ourselves against the battering wind. A notice proudly proclaims the inception of an automatic telephone exchange officially opened by a local dignatory in 1988. This village has certainly seen some changes in Miguel’s lifetime.

The first house we come to in the deserted square is a large refurbished building squatting at the very edge of the precipitous south facing slope. This is the house of Gregorio, a lifetime friend of Miguel and purveyor of fine costa wine. Miguel presses the doorbell and we can hear a cheerful chime from deep within the house. Eventually the door opens and Carmen, Gregorio’s wife, opens at first cautiously, then with beaming recognition she ushers us inside. She wears the typical floral cotton pinafore of the Andalucian housewife. The garment matches her purposeful manner as she invites us into a small neat room crowded with its round table and numerous upright chairs. We sit and hear the approaching clomp of Gregorio’s walking frame. He has recently had a knee operation and progresses slowly towards us from the kitchen. There follows intense conversation about operations, mutual acquaintances and much bemoaning about Spain’s economic plight.

Both men have lived off the land and indulge in arcane complaints about the falling price of their produce which excludes me. The ritual soon closes as we must not tire Gregorio and there is the bodega to visit. Carmen leads the way across the square followed by the shuffling Gregorio and the two of us bringing up the rear.

We arrive at the door of an ancient building which boasts faded blue shutters and washed out terracotta walls. Long before the automatic telephone exchange, this building stood as a proud monument to the industry of the village’s wine producers. Car men fits the ancient key and soon opens the door to the cavernous interior. We stand at the threshold peering into the dark inner cavern, overwhelmed by the heady rushing smell of the treasure within, contained in huge wooden barrels. Our eyes grow accustomed to the low light and view the paraphanalia. On the wall there is a ladder made of agarve stems bedecked with odd bits of esparto hanging like talismans along the rungs below the sloping beams. Huge grimy carafes cluster round the base of the barrels and it’s as though time has stood still within these walls. Carmen pours us a sampler then fills a plastic bottle for Miguel to take away as a gift. Outside, the light brings out the deep ruby tones of the bottle’s contents and with greater ceremony, this time, the bottle is carefully placed, precious cargo, on the back seat of the car.

men fits the ancient key and soon opens the door to the cavernous interior. We stand at the threshold peering into the dark inner cavern, overwhelmed by the heady rushing smell of the treasure within, contained in huge wooden barrels. Our eyes grow accustomed to the low light and view the paraphanalia. On the wall there is a ladder made of agarve stems bedecked with odd bits of esparto hanging like talismans along the rungs below the sloping beams. Huge grimy carafes cluster round the base of the barrels and it’s as though time has stood still within these walls. Carmen pours us a sampler then fills a plastic bottle for Miguel to take away as a gift. Outside, the light brings out the deep ruby tones of the bottle’s contents and with greater ceremony, this time, the bottle is carefully placed, precious cargo, on the back seat of the car.

Just as we thought we had reached the world’s summit, we leave the sleepy village behind and head up towards Haza de Lino at 1280 metres of altitude. Now ancient vines become evident and we pass dense holm oak and the denuded cinnamon coloured trunks of the roadside cork trees. Figs also stretch out along the road’s edge retarded in their budding at such a cold height. We run the gauntlet of stolid white cortijos and the deserted Jabali restaurant winding eastwards then stopping to gaze across to the backcloth of the Alpujarran villages encrusted below the snowline beyond the dark footlamps of the ancient low growing vines.

“It’s all changing” Miguel assures me in what seem like warning tones. Many of these vines are abandoned. The youngsters aren’t interested. Two of his daughters have joined the flocking ranks of young Spaniards seeking education or employment in foreign lands. I try to imagine him visiting his daughter, Lola, in London and cannot envisage a more extreme contrast between that vast metropolis and the sleepy twinkling village of Gualchos where he has always lived.

Then suddenly, as if stage managed, we come across the amazing presence of a ploughman driving a team of mules using a hand held plough so much like the photos I had seen of Miguel in that very occupation more than 50 years earlier. We have to stop and exchange greetings. The man wipes his brow, smiles to us then turns his team against the unfriendly slope between the low close ranks of the knotted vine plants. Soon that won’t be seen Miguel states and there is a plaintive quality to his tone.

Finally we reach our destination. We have headed northwards along the Cadiar road stopping at the roadside Venta past the huddle of houses where we had come with another friend, sadly no longer with us to meet the neat diminutive figure of Manuel Guadiano. It is over three years since we first met him, in search of costa wine and at first we are disappointed to find his door locked. We call out and we are rewarded by the disembodied voice which reaches us from the yard at the back of the house.

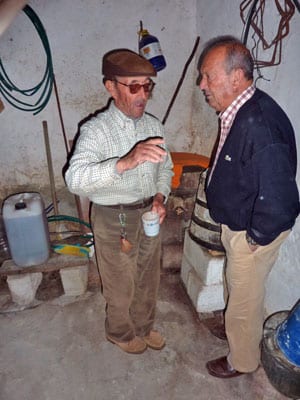

Manuel emerges, tiny and weathered. He wears no teeth and as he recognises us, his face erupts into a gargoyle’s rictus and his inordinately large hands reach out to clasp each of ours in turn.  We sit in his porch beneath the cramped partridges in their cruel cages and reminisce about our previous visit. We have brought him a photo from that time of him and Miguel and David who is no longer with us. There is further reflection on how things have changed. Manuel talks of early memories, his family, the Civil War. He and Miguel huddle conspiratorially. They blame Socialism for the country’s plight and as if to prove his case, Miguel bypasses the present incumbent and harks back to the term of Felipe Gonzalez.

We sit in his porch beneath the cramped partridges in their cruel cages and reminisce about our previous visit. We have brought him a photo from that time of him and Miguel and David who is no longer with us. There is further reflection on how things have changed. Manuel talks of early memories, his family, the Civil War. He and Miguel huddle conspiratorially. They blame Socialism for the country’s plight and as if to prove his case, Miguel bypasses the present incumbent and harks back to the term of Felipe Gonzalez.

I bite my tongue and remind Manuel of the nectar he keeps hidden away in the inner sanctum of his bodega. It is just what is needed to lighten the mood, and so passing through his labyrinthine dwelling, past tasteless knickknacks and numerous photographs of weddings, ancestors and first communions, we arrive at that secret den where the naked light bulb still hangs but changed since our last visit to an energy saver as a concession to a modern age or economic expedient in this time of “La Crisis”. The small squat barrel dominates the corner of the room and knowing its contents, it holds all the charisma of Aladdin’s lamp. Manuel finds a cup and with shaking hand, manipulates the tap on the barrel allowing the amber treacle to slurp into the vessel. We carry it outside and he decants it into 2 small glasses. Hidden from the light of day since 1973, it resonates with fruit and power like no other wine we have had from the Contraviesa. No words are necessary to express our appreciation as we drain the glass and smack our lips.

We leave the old man in his 90th year waving to us as we turn Southwards and head off eventually passing the wealthy settlements of Albondon and Albuñol with their Moorish sounding names then West along the coast along the low road flanked by the furious sea and slowly home to Gualchos.

We arrive in the village to the ominous leaden clonk of the church belling announcing a recent death. Miguel’s neighbour passes by. Who has died? Isabel, La Rubia. She was my first neighbour when I came to the village over 10 years ago. She was one of life’s originals with her herds of goats, gangs of cats and rabbits and yard full of flapping pigeons.

Her generation are gradually passing and as the younger people turn away from the old farming methods in search of new opportunities and different kinds of lives from those of their parents, I can understand Miguel’s wistful comments and can’t help feeling we have reached the end of an era.

Wonderful

It really is a delight to read your articles, to imagine places and persons , – like being back in Gualchos.

Yours

Thyra Larsen from Denmark , – in Gualchos Calle del Mar

Very beautiful,very true(you painted a picture with your words)and very sad.

Spain is beautiful for eating and drinking, running and just dozing under a tree. If I could persuade my other half, I’ld buy a house somewhere in Malaga – say, around Antequera – and spend most of my time there.