WHAT’S the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word ‘anarchy’ – defined as ‘a state of disorder due to the nonrecognition of authority’?

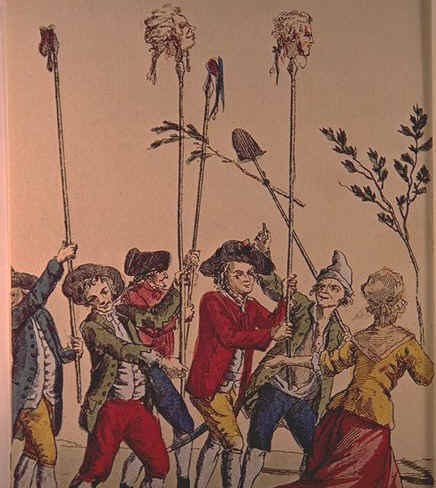

France’s infamous Reign of Terror, perhaps, or the present-day situation in Venezuela or Syria?

If you are the parents of hormonal teenagers (gulp!) you probably know a thing or two about it!

Whatever your perception, it might be surprising to know that Spain has a long tradition of ‘disorder due to the nonrecognition of authority’.

In the middle of the 1800s, political ideologies long thought to be extremist were brought to Spain from the hotbeds of revolutionary Europe.

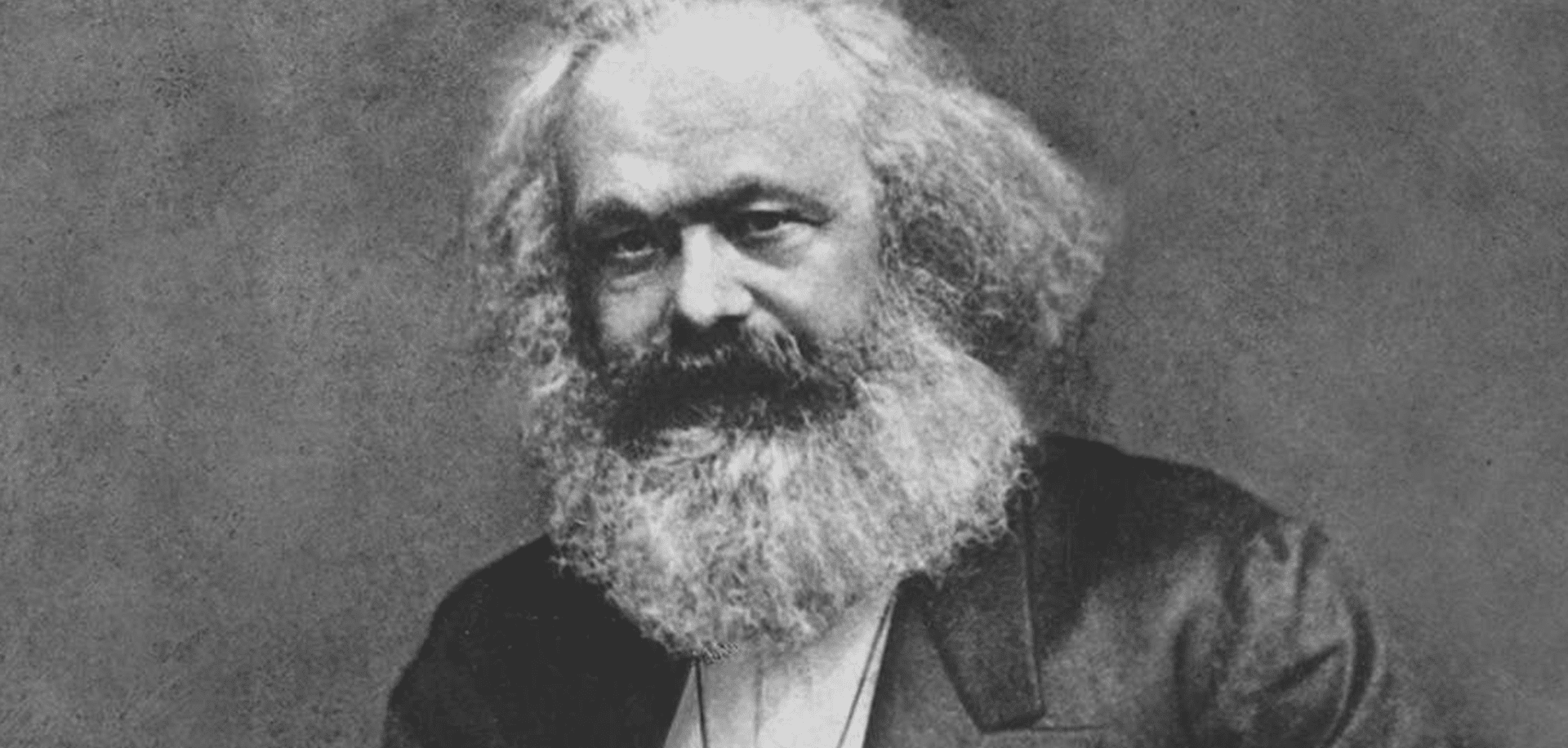

The French Revolution, Karl Marx, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Locke etc. collectively resonated with those who sought fairness in society.

From early on, Spanish style ‘anarchists’ believed strongly in the class struggle against the cabal of the church, the state and the landed elite.

They saw these powerful forces exploiting workers, the poor and the landless, resulting in grinding poverty, starvation and war.

Early Spanish anarchists opposed any authority that claimed the right to have power over anyone else.

Anarchy first gained a foothold in Catalunya, then a crucible for proletarian and trade union rebellion.

Revolutionary ideology was propagated in neighborhood cafes, by radio broadcasts and newspapers, propaganda tours and travelling libraries.

The oppressed and marginalised throughout Catalunya, and later the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, were very receptive to an ideology that opposed authority; namely the ‘state’ with its brutality and corruption; unchecked capitalism with its grand wealth and wretched poverty; and the coercive institution of organised religion.

In Andalucia, however, the conscious ‘non-recognition’ of authority began to take on a new and strangely positive dimension.

In the run-up to Spain’s greatest nightmare, The Civil War, anarchists, communists, socialists, unionists and a melting pot of political factions joined forces against entrenched authority.

The social structure of Andalucia in the early 20th century, being primarily agrarian, required a division of labor based on gender roles.

Men participated in field tasks such as harvesting crops, animal care, irrigation, using farm equipment, etc.

Fun Facts

• Anarchy: from medieval Latin/Greek anarkos. an-(without) + arkhos (ruler).

• The guillotine became the symbol of anarchy during France’s Reign of Terror. It is estimated over 40,000 lost their heads to its unforgiving blade (ouch!) including Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and Maximilien Robespierre.

• Vivir la Utopia is an excellent, informative documentary film by Juan Gamero (1997). It consists of 30 interviews with surviving members of Spain’s Anarchist movement. It can be viewed for free on YouTube.

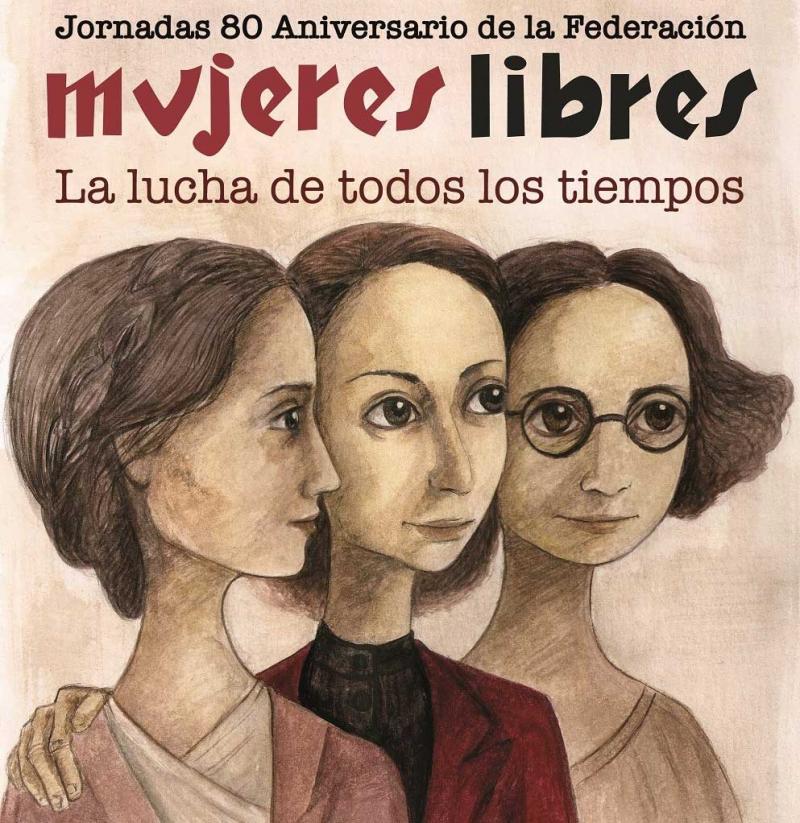

• ‘Anarcha-feminism’ is still a recognised term in today’s feminist movement. Combining anti-authoritarianism and feminism, the concept was popularised by Spain’s Mujeres Libres organisation.

Women mostly participated in farmhouse tasks like tending family gardens, preparing and preserving food and maintaining the home.

They were expected to be the ‘Angeles del Hogar’ (angels of the hearth) at home and the Perfecto Casada (perfect wife) in their marriage.

Socially, the conditions for agricultural women was uniquely oppressive and they could be forced into arranged marriages without their consent.

Once married and without her husband’s approval (called ‘permiso marital’), a woman was prohibited from ownership of property or travel away from home.

There were punitive penalties for adultery, while divorce was impossible.

Single women could not leave the farmhouse without a male chaperone.

Most women were financially dependent on men and had virtually no access to education.

Conditions for women outside Andalucia were, on balance, slightly better.

For example, Catalunya had a thriving textile industry where over half of the workforce were women.

In Madrid, Zaragoza and other northern cities, women were able to find at least some degree of autonomy in domestic work outside the home, and in communications.

In Andalucia however, women found themselves in a deplorable state.

In 1936, women in Malaga, Cadiz and Seville began to develop an extensive network of organisations dedicated to the idea of women’s liberation.

With very little to lose and under such detestable circumstances, women activists travelled through the Andalucian countryside to set up rural collectives where they organised schools, literacy programmes and women-only social clubs and newspapers.

More importantly, the women of Andalucia were some of the first to join forces in alliance with the larger Republican (anti-Franco) constituents of communists, socialists, and unionists (e.g. The Popular Front).

These rural women were dedicated to the belief that women’s issues were inseparable from the social upheaval of the day.

They passionately argued that the double struggle for women’s liberation AND Spain’s greater social revolution (The Civil War) were equally important and should be pursued in parallel.

The women’s movement that took hold here was not confined to southern Spain.

In the north, one group in particular, Mujeres Libres (Free Women), self-described as an ‘anarcho-feminist’ organisation emerged as a strong leader in their dedication to empower working class women.

Their stated mission was to free women from ‘the triple enslavement to ignorance, as women, and as producers’.

The group soon had over 30,000 active members.

They successfully articulated visions of a new social life for women.

Mujeres Libres sponsored programmes on maternal and child health, day-care, female biology and sexuality.

They pointed out that virtually all education for women had been controlled by the Catholic Church.

Mujeres Libres was a pioneer in openly discussing taboo subjects like sexual freedom, birth control, abortion and co-habitation and how these issues could not be separated from the greater social revolution.

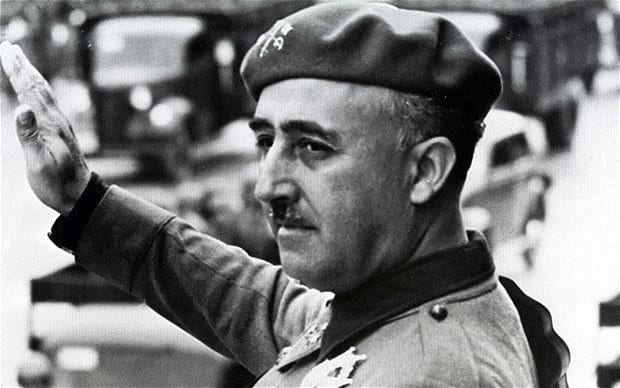

As any student of the Spanish Civil War will tell you, things did not end well for the Republicans i.e. the socialist, communists, unionist and anarchists.

With Franco’s victory in 1939, Republican sympathizers were at the very least silenced, went underground or exiled.

More likely, they were executed.

But the liberation ideology of women, born of their stifling experience in Andalucia, was a planted seed that would come to fruition later on in the late 20th century.

It has been said that the en masse beheadings and anarchy associated with France’s Reign of Terror was a necessary precursor to the ideals of The Enlightenment.

(Those who lost their head would certainly disagree!).

And who can possibly predict the outcome of the chaos in present day Venezuela and Syria?

As for advice for parents on their hormonal teenager’s inherent ‘nonrecognition of authority’? Good luck with that….

A learned, interesting article, particularly on the subject of Anarchy. However it neglects the currently continuing two-year reign of Anarchy in Northern Ireland. Not surprising really as no-one else seems to have noticed either. Goes to show that Anarchy can work quite well.