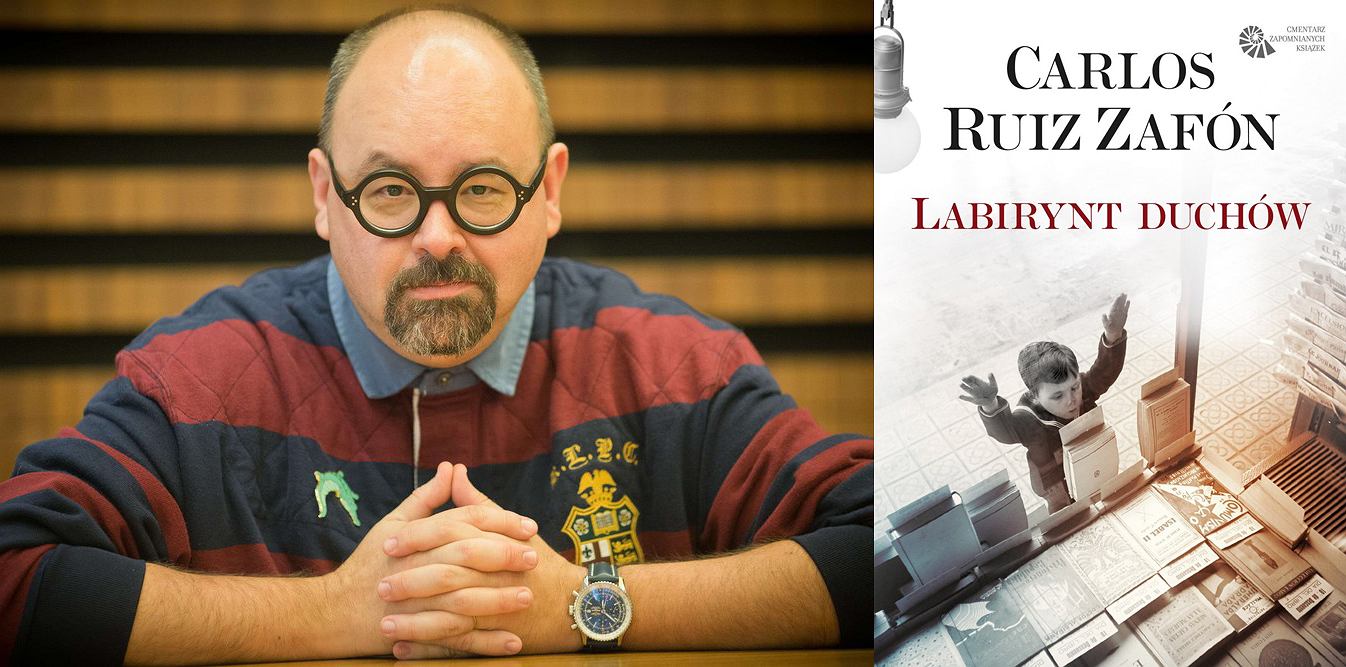

CARLOS Ruiz Zafon needs no introduction. Arguably the most recognised contemporary writer in Spain, he has an equally successful international reputation.

Translated into over 50 languages, literary critics have often compared Zafon to none other than Miguel de Cervantes in style, popularity and literary impact.

Carlos’s trilogy The Cemetery of Forgotten Books series, combined with his most recent book The Labyrinth of the Spirits (El Laberinte de los Esperitos), are perennial best-sellers around the world.

Zafon’s series arrived on the publishing scene with contemporaries Dan Brown and J.K. Rowling. Their popular genre shared countless tomes: tormented characters, often seeking knowledge centered around secrets to be found in books and archives. ‘Tales within tales’, giving way to ‘books within books’, with multiple subplots become a flourishing subgenre with the reading public.

Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and Rowling’s Harry Potter would go on to become record-breaking hits at the cinema box-office. Curiously, Zafon rejected the many lucrative offers to turn his books into movies and he had some very strong opinions as to why….

Carlos has been consistent with his personal mission to encourage people to recover the pleasure of reading. In our flashy, crazed world of the internet, smart phones, video games and digital streaming, Zafon believed the joy of reading was being forgotten.

“Reading”, said Zafon, “is a primal force in which we, the readers, collaborate with the authors to create adventures, empathy and memories not unlike those of our real lives.” He believed ‘books are mirrors to the soul’ and by reading we develop stronger analytical skills by taking note of detail.

It is perhaps ironic that before Carlos Ruiz Zafon became an international best seller, he began his career as a screenplay writer in the movie capital of the world – Los Angeles, California.

He was an avid fan of the film noir genre and had notable success as a Hollywood screenwriter. He would be the first to admit this genre, marked by moods of pessimism, fatalism and menace was a major influence on his later written work.

But Carlos saw a disconnect between storytelling as novel verses adapting that same story to a movie. Movies, he believed, are experienced by the audience in one 90 to 120 minute block of time but books may be picked up and put down, pondered and digested, multiple times before completion.

Carlos believed that, by reading, content could be taken in at intervals dictated by the reader’s ‘rhythm of consumption’.

He once famously said that unlike movies, ‘books have no beginnings or endings – only points of entry’.

Since something is lost from the transition from books to movies, Carlos was emphatic in not wanting to spend the time remaking his stories into another media.

He claimed that developing characters and interlocking plots so precariously, he feared his stories would ‘explode’ if he tinkered with them by adapting them to the big screen.

Zsofon believed that by reading, one can better picture his books ‘shot by shot’, the way he designed them because that is central to the reading experience.

Tragically, Carlos Ruiz Zafon, that prolific Spanish novelist who has been compared to Cervantes, succumbed to cancer last year and died in his prime at age 55.

He will forever be remembered as an outlier in the world of storytelling. It is rumored that Zafon took the time to declare in his last will and testament that his books ‘never, never, never’ (his words) be made into movies.

Rest in Peace Carlos….

READ MORE:

- LONG READ: Jack Gaioni reveals the fascinating story of Lola Montez, the fake Spanish dirty dancer who captured a…

- Superstition emptied a Spanish village in the 14th century before turning it into a must-visit festival, discovers Jack Gaioni

- Basque magic: How Spanish children ended up playing in English teams before ‘foreign players’ became a thing

A somewhat elitist stance. Much magical thinking would be lost to those who can not or will not read. The oral tradition of tale-telling gave way to print, allowing multitudes to access stories and information. Now we have various electronic means of communication, including movies.

Where’s the harm? Some people would never have known of the myriad stories available, if they had not been made into movies. (An art form in itself)