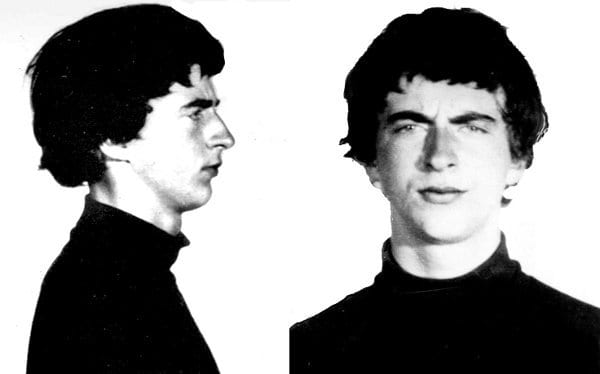

SCOTTISH history is awash with legendary figures but Stuart Christie – a young Glaswegian involved in a plot to assassinate General Franco – is not the first name that springs to mind.

Nevertheless, on August 11 1964, this 18-year-old idealist was arrested in Madrid for attempting to do just that.

And in a further bizarre twist, the young suicide bomber was found to be carrying a kilo of explosives under a woolly jumper knitted by his grandmother.

By way of swashbuckling plots and tales of derring-do, the coup was straight out of a Hemingway or le Carré novel. Indeed, Christie reveals all its intricacies in his intriguingly-titled autobiography, ‘Granny Made Me An Anarchist’.

Born and raised in Glasgow, Christie became involved in left-wing politics at a young age. Disillusioned with the Labour Party, his involvement with the city’s Anarchist Federation brought him into contact with operatives from Defensa Interior, an organisation dedicated to fighting Francisco Franco.

It was the 1960s and Franco was in his third decade of power. The presence of a dictatorship in Western Europe, even at the height of the Cold War, was always an embarrassment. Spain was a social and economic pariah on the continent, strategically tolerated by Western powers only because of the Generalissimo’s hatred of communism.

Nevertheless, the scale of his repression, torture and murder made him a natural target for political campaigns and the morally aware.

When Christie moved south to London to work as a sheet-metal apprentice, he came into contact with Spanish anarchists in exile. They convinced him he had to do more than pay lip service or partake in marches to defeat Franco.

‘Much as I liked girls and dancing, I felt it was impossible to remain silent and inactive in the face of a fascist dictator’s repression of his country’s people,’ he wrote in his memoir. ‘It was time for action.’

The young man’s motivation, while revolutionary and in line with general sentiment against the dictator, was also inherently idealistic. It might have been Spanish anarchists who lit the path but, as the title of his autobiography suggests,he was also strongly influenced by, his formidable grandmother Agnes.

Agnes, a strict Presbyterian, helped Christie’s mother to raise him after his father walked out. It was she who encouraged a passion for social justice and who provided ‘a moral barometer which married almost exactly with that of libertarian socialism and anarchism, and she provided the star which I followed.’

So taking heed from his grandmother and inspired on by the likes George Orwell who fought with the International Brigade against fascism in the Spanish Civil War, he acted.

Christie left London for Paris where he met members of the Defensa Interior organisation. His assignment was to deliver explosives to Madrid for an attempt on Franco’s life, without actually knowing the details of the plot to blow up the dictator at a football match. Although Franco died ten years later, the plot had particular significance as the last of at least 30 attempts on the fascist leader’s life.

By Christie’s admission, his hitchhiking effort to Madrid and general appearance were not proper spycraft: ‘With the plastic explosive strapped to me, my body was improbably misshapen,’ he wrote.

‘The only way to disguise myself was with the baggy woollen jumper my granny had knitted to protect me from the biting Clydeside winds. At the risk of understatement, I looked out of place on the Mediterranean coast in August.’

The circumstances were against him too: Defensa Interior was already heavily infiltrated by the Spanish security services. In Madrid, en route to meet his contact, an empty taxi pulled up to the pavement beside him. When the driver appeared to invite him to get in, he realised it was an unmarked police car.

‘As I steeled myself to make a dash through the crowds I was suddenly grabbed by both arms from behind, my face pushed to the wall and a gun barrel thrust into the small of my back. I tried to turn my head but I was handcuffed before I fully realised what had happened. It was all over in a matter of moments.’

Christie was arrested along with his Spanish contact Fernando Carballo Blanco. In a humorous sidebar to the story, it was falsely reported that he had been wearing a kilt at the time which confused the Argentine press into describing him as ‘a Scottish transvestite’.

Charged with ‘banditry and terrorism’, he faced a military trial and a possible death sentence by garrotte, a particularly nasty form of strangulation.

Christie wasn’t tortured, as was common in Franco’s Spain. He signed a confession four days later and was sentenced to 20 years in prison. Blanco got 30 years and held the awkward distinction of being the last political prisoner of the Franco regime.

Because of his youth and nationality, Christie’s involvement received significant international attention from the likes of Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre, among many other social activists. In prison, he studied for his A-Levels in history, English and Spanish and met other anarchists.

His incarceration prompted global protest. He wrote, ‘I was told by the British consul that there were demonstrations all over the world. The most beneficial thing was that my arrest provided a focus for what Franco was doing.

Here he was trying to pass himself off as an old avuncular gentleman on a white charger while in fact, he had all these political prisoners, thousands of them who were tortured and some of them killed. The monster was growing again.’

He served three years before international pressure and public protests in the UK forced Spain to release him. The official reason cited by the Spanish regime was a plea from Christie’s mother.

Later in life, Christie was glad that the assassination attempt was unsuccessful. ‘The arrest turned out for the better. I probably did more for the cause of anti-Francoism by not killing him. There is that law of unintended consequences.’

It’s impossible to deny that Christie was brave and that his sense of justice led him into great danger. Did his idealism overtake an appreciation for the perils of a fascist state? Perhaps.

But then again, that was the case for the 2,400 British volunteers, 549 of them Scottish, who travelled to serve in International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Quite rightly, they’re honoured with a statue in Glasgow.

History knows how fascism in Spain died with Franco, but it’s remarkable to muse what might have happened if it had stopped sooner, thanks to a young Scot.