By Wendy Williams

IT has long been recognised that the Iberian peninsular is a treasure trove of historical wonders.

Its wealth of prehistoric sites boast some of the most important finds in Europe and new discoveries from the age of the dinosaurs and prehistoric man come almost by month.

The most recent came in Teruel, when researchers at the now world-famous Dinopolis Foundation found a femur – the largest ever found – that would have belonged to a giant Turiasaurus Riodevensis that lived 145 million years ago.

Making the animal 98 feet tall – or as large as a house – it is further proof that Spain really is the land that time forgot.

Andalucia itself is said to be second only to Africa’s Rift Valley for prehistoric finds.

Among its secrets is evidence of the first arrival of man in Europe, as well as the last stand of the Neanderthals in Gibraltar.

In Orce, near Granada, an industrious dig has not only recently found Europe’s oldest man, but also the bones of rhinos, hippos and elephants that once roamed the province.

And then there are the numerous Stone Age cave paintings, so good, that the European Union has just designated a special route taking in the best of them.

While there are an incredible 700 sites designated as important prehistoric rock art sites by UNESCO, they have now picked out the best 10 for the tour.

One of the most exciting is the Tabla del Pochico cave in Aldeaquemada, a small village of 600 souls, in Jaen’s Despeñaperros Natural Park.

Others include Los Letreros in Velez-Blanco (which features the painting of el Indalo, now adopted as the symbol of Almeria), as well as the Doña Trinidad cave in Ardales.

Traditionally the home of archaeological Spanish finds has been in the Sierra de Atapuerca, east of Burgos, in the north of Spain.

At one site – the Sima de los Huesos, or ‘Pit of Bones’ – archaeologists have traced over a million years of human evolution.

Just last month a study of bones found nearby has revealed that cannibalism was a normal part of everyday life for humans living around 800,000 years ago.

Among the bones of various animals, archaeologists uncovered the remains of at least 11 children and adolescents, which all showed signs of cuts made by stone tools where the flesh had been sliced from the bones.

And it wasn’t just for the purposes of hunger. According to the co-author of the study, Jose Maria Bermudez de Castro, since the surrounding area would have provided a rich source of food, it is likely they ate other humans for strategic reasons too.

“It was more likely used as a way of dealing with competition from neighbouring tribes,” he explained to the Olive Press. “And children were the easiest targets.”

The first discoveries of prehistoric animal fossils in the mountainous area occurred in 1899 during construction on a railway line.

But it wasn’t until the 1970s that a Madrid palaeontologist identified some of the bones as having belonged to humans, and even then it was 1984 before work began on the site.

Since then, the archaeological importance of Atapuerca has been firmly established, due to both the age of the remains, and the fact they span hundreds of thousands of years revealing countless details of how ancient man lived.

In 1997, for example, archaeologists unearthed part of the skull of a young male, identified as belonging to a new species of human given the name Homo antecesor, or Pioneer Man, which was said to be the ancestor of both modern humans and Neanderthals.

Following this, in 2003, a further discovery was made that shook the archaeological world and suggested humans had lived on the continent much earlier than had been previously believed.

The exact date of Europe’s first humans had long been a hotly debated topic.

Andalucia is second only to Africa for prehistoric finds

But in 2003 the Atapuerca team dated a small piece of jawbone from up to 1.3 million years old, by far the oldest in Europe.

This meant that humans had lived on the continent some 500,000 years longer than previously thought.

However, there was another discovery, nearer to home – in Orce, in Granada – that apparently makes it the real ‘Cradle of European man’.

It happened in a dig led by Professor José Gibert in 1982, when students unearthed an unusual bone fragment, which a year later, was announced had belonged to a human child.

Even more significantly it was claimed it could be up to 1.6 million years old, pre-dating anything previously found in Europe.

It has caused huge controversy with rival experts sometimes claiming that the fragment – nicknamed La Galleta, or ‘the cookie’ – was not even of human origin, but belonged to a horse or donkey.

In spite of this, excavations have continued in the Orce region, in an attempt to uncover further evidence to back this claim.

Recently, investigators found the remains of hippos, rhinos and elephants which they believe were eaten by local hunters.

According to Project Director, Robert Sala, these are even more important than the finds at Atapuerca and are “the richest and best in Europe” as they strongly support theories that mankind was living here 1.3 million years ago.

Curiously, if we head west to Gibraltar we can find yet another interesting strand of European prehistoric history.

For it was here in 1848 that the last remains of Neanderthal man in Europe were found.

Curiously the discovery was not given much weight, until eight years later a team of quarry workers in the Neander Valley in Germany (hence the name) unearthed a similar skull.

It was only from then, that the Neanderthals were actually recognized as a separate species.

And it took experts many years to discover that the race was the “missing link” between apes and modern man.

Previously, research suggested that when Homo sapiens (from which all mankind today is descended) arrived from Africa some 40,000 years ago, they displaced the Neanderthals from Central and Western Europe.

But new findings revealed primeval man survived for longer than was previously accepted and the Neanderthals actually lived alongside modern humans as our contemporaries, for thousands of years.

Scientists have discovered eight caves where Neanderthal man once lived.

One of the greatest discoveries is the ‘Gibraltar Child’, discovered in 1926 by the first female professor at Cambridge University, Dorothy Garrod.

She recovered five skull fragments followed by the later discovery of the jaw.

Based on studies of the teeth, Garrod originally believed the child was aged five, but it is now thought the infant was in fact younger and died aged three or four.

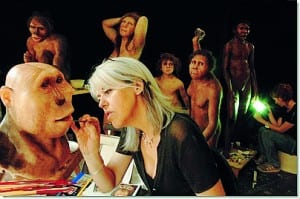

Fascinatingly, French-born artist Elisabeth Daynes has recently been able to sculpt an incredibly life-like reconstruction of the child based on 3D computer images.

And the reconstruction, which took approximately two months to complete, is currently on display in the Krapina Museum in Croatia.

Subsequent Neanderthal discoveries in Gibraltar have pointed to the fact that this is not only the place where Neanderthal remains were first found, it may also be the place of their final refuge.

New findings show early man and Neanderthals lived as contemporaries

In Gibraltar alone, sciClive Finlayson, director of the Gibraltar Museum, has uncovered evidence that the Neanderthals survived longer in Gorham’s Cave (named after Captain Gorham, who discovered the site in 1907) than anywhere else.

As he points out in his book The Humans Who Went Extinct: Why Neanderthals died out and we survived, recent radiocarbon data from Gorham’s Cave suggests Neanderthals were still living on Gibraltar around 24,000 years ago.

Crucially, this is 5,000 years after it was thought they had died out.

And palaeontologist Chris Stringer, of the Natural History Museum in London, supports the theory that Gibraltar may well have been the dying species’ ‘last outpost’.

Exactly why the Neanderthals died out has, of course, been a source of much speculation. But most recently it has been argued the destiny of the Neanderthals and Modern man was sealed by climatic factors and that it was actually just a matter of luck that we survived, while they perished.

Better at surviving the mini ice age that came at that time, it begs a certain fascinating thought; had the climate not changed in our favour perhaps we would not have been around today.

As it is we are the lucky ones; the ones left with a rich abundance of archaeological sites to help discover the final definitive proof of evolution.

And so it is a good thing that UNESCO has decided to protect these treasures and put them pride of place on a new cultural route.

Surely we now owe it to the Neanderthals to uncover their heritage and bring them back to life.

Excellent.

98 feet tall ? I think you may mean ‘long’.

Still very impressive, but we are talking about a real creature here, not Godzilla