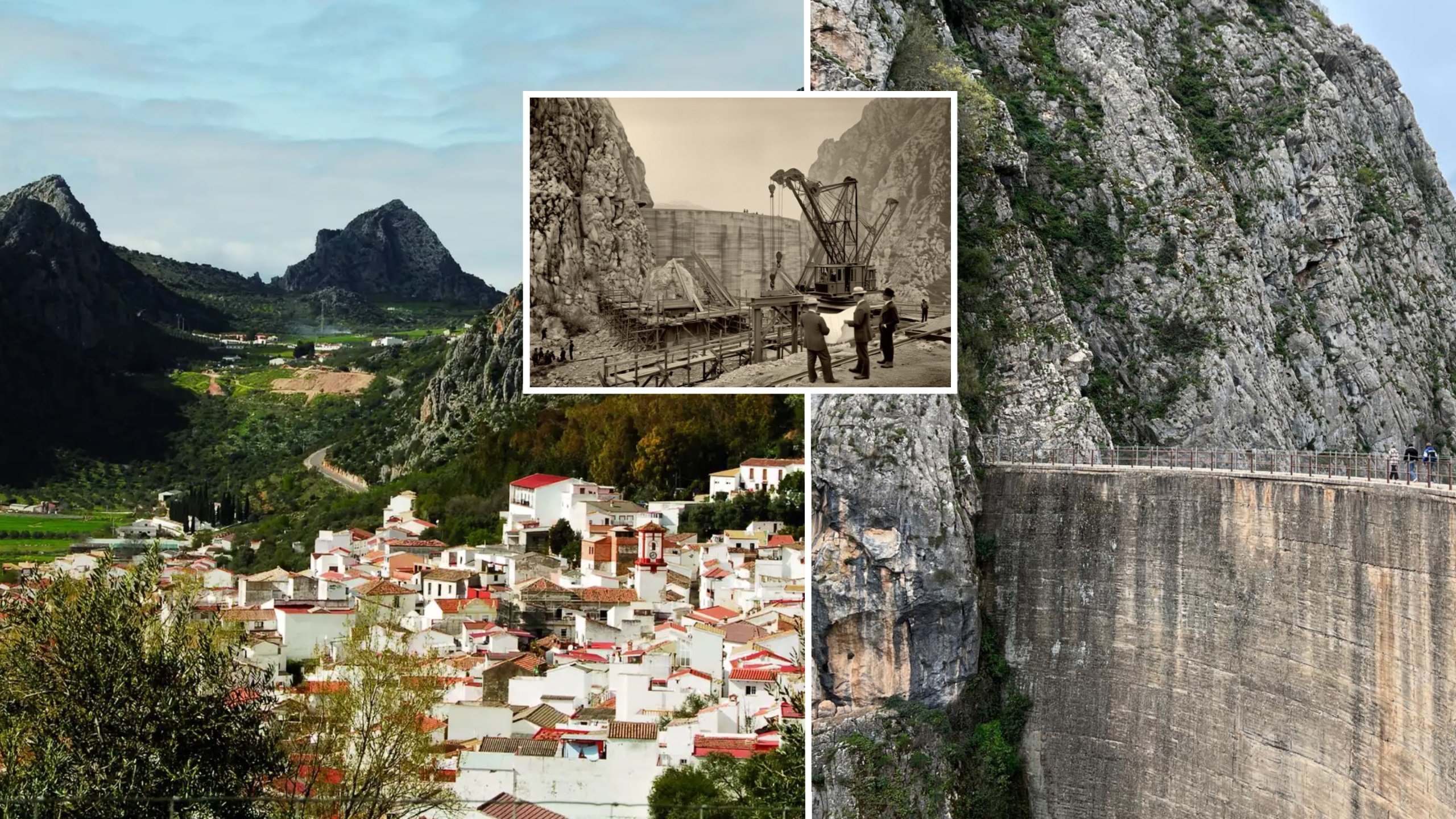

FOR a century, the Montejaque Dam has stood as a silent, bone-dry monument to human hubris—a spectacular engineering failure hidden in the mountains above Ronda.

To the locals, it was the ‘Ghost Dam’; a concrete folly that could never hold water. But this weekend, the ghost has woken up.

As Storm Leonardo battered the province, something unprecedented happened. The vast subterranean cave systems that have drained this reservoir for 100 years finally choked.

Saturated to the limit, the mountain stopped drinking the water, and the dam began to fill.

Now, this ‘useless’ masterpiece is the source of a very real and present danger.

With the water lapping at its spillways for the first time in history, the pressure on the limestone gorge is immense.

The terrifying ‘tremors’ reported by residents in the valley below are the sounds of a geological system pushed to breaking point, forcing the evacuation of 200 souls from the Estacion de Benaojan.

To understand the scale of this threat, one must look back at the extraordinary history of the structure itself.

A Cathedral of Concrete

If you traverse the winding MA-8403 from Ronda towards Sevilla, climbing into the imposing limestone amphitheatres of the Sierra de Grazalema, you will eventually confront it.

Standing 83 metres high, the Presa de Montejaque is a breathtaking sight. Even today, it possesses a stark, brutalist elegance.

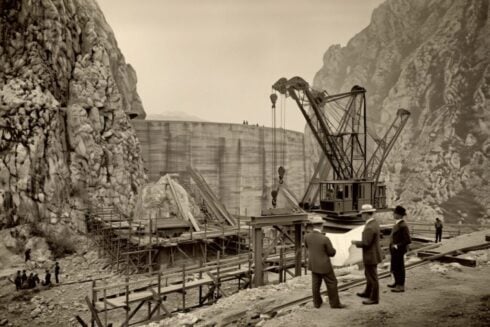

Commissioned in 1924 by the Sevilla Electricity Company, it was born of the feverish industrial optimism of the Roaring Twenties. Hydro-electric power was the future, and Andalucia’s rushing rivers were the fuel.

To realise this vision, they hired a Swiss architect named Grüner. His design was revolutionary. Breaking away from the traditional masonry blocks of the 19th century — which were slow, expensive and heavy — Grüner utilised the ‘wonder material’ of the age: reinforced concrete.

This allowed for a daring, curved design (an arch dam) that drove the pressure of the water into the canyon walls rather than relying on the sheer weight of the wall itself.

It was the first of its kind in Spain and, at the time, the highest dam in the country.

It took just nine months to build—a lightning speed for such a colossal structure. It was to be a triumph of modern engineering, a slender, joint-free shield that would power the homes of Sevilla.

It was a masterpiece. And it was a disaster.

The Fatal Flaw

Grüner and his team had made a catastrophic oversight. In their rush to conquer the landscape, they had failed to understand it.

The Sierra de Grazalema is not solid rock; it is karst. The limestone mountains are like a sponge, riddled with cracks, fissures and vast underground cathedrals carved out by millions of years of rainfall.

Lurking directly beneath the dam’s foundations was the Hundidero-Gato system—one of the largest and most complex cave networks in Europe.

From the moment the sluice gates were closed in 1924, the dam was doomed. The reservoir was essentially built on top of a giant plughole.

No matter how much it rained, the water simply vanished, percolating rapidly through the porous rock and roaring through the subterranean galleries to emerge miles away at the Cueva del Gato (Cat’s Cave).

For decades, engineers tried to plug the leaks with asphalt and cement, but the mountain always won. By the 1940s, the project was abandoned.

The Sleeping Giant

For the last 80 years, the dam has served only as a curiosity for hikers and a nesting ground for the griffon vultures that circle lazily in the cloudless skies above. It became a part of the landscape—a harmless, dry wall in a wild paradise of evergreen oaks and limestone outcrops.

But nature has a way of rewriting the script.

The relentless deluge of Storm Leonardo has achieved what a century of engineering could not: it has sealed the plughole.

The cave system is so overwhelmed with water that it has backed up, transforming the empty reservoir into a deep, volatile lake.

The water that usually flows harmlessly out of the Cueva del Gato — a popular swimming spot where locals like the legendary Cristóforo dive into the freezing waters to cure their hangovers — has turned into a torrent.

Today, the ‘Dam with a Difference’ is no longer a quirk of history. It is a loaded weapon pointed at the valley below, reminding us that while we can build our concrete monuments, the mountain always has the final say.

Click here to read more Malaga News from The Olive Press.