THE finished version of Spain’s €5 billion ‘Mediterranean Corridor’ rail network has finally been announced — but not to universal fanfare.

While some regions are celebrating their newfound connectivity, there are some glaring omissions that have already sparked outrage.

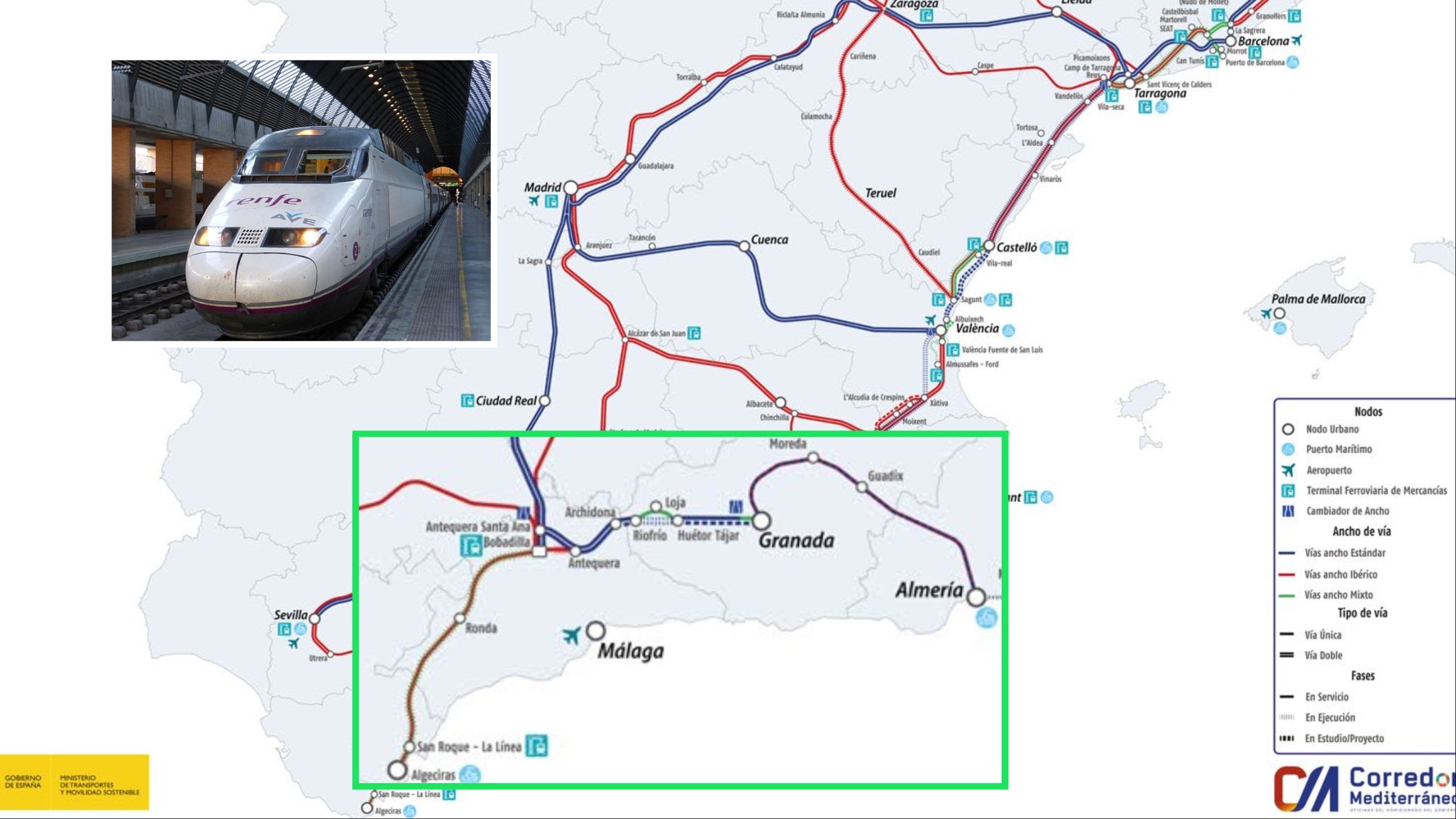

Transport minister Oscar Puente, speaking in Valencia during the annual ‘Quiero Corredor’ event (responsible for creating a cringy video extolling the virtues of the train line), confirmed works are already underway across every region included in the new train map – while those left out languish.

He said the government had sped up construction in the past two years, ploughing in €2.6 billion since 2023 and forecasting a further €1.3 billion by the end of 2025.

In total, €5.4 billion has been splashed on the corridor since 2018 – much of it backed by EU funding – directed at linking Spain’s Mediterranean ports and cities with the rest of Europe.

READ MORE: Spain shoulders 20% of all GDP growth in the eurozone as traditional powerhouses stagnate

The winners

Some of the biggest beneficiaries of the much-hyped project will be found in Murcia, where a large share of the recent spending has gone into a new high-speed line connecting it with Almeria.

A 200km stretch of track, backed by €3.6 billion in funding, is currently under construction, with work advancing between Murcia and Lorca and along the Vera to Almeria section.

One of the most significant milestones of the corridor will come in 2026, when Murcia’s El Carmen station opens as a through-station following a €600 million rebuild.

The change will remove a long-standing transport bottleneck and allow continuous high-speed services to run between Alicante and Valencia in the north and Lorca and Almeria in the south, forming – in some ways – a true Mediterranean train corridor.

READ MORE: Spain’s housing crisis will continue for years because ‘house building is just not profitable’

Further north, the coastal section between Alicante, Valencia, Castellon and Tarragona is now the most advanced part of the corridor, with upgrades already in service and additional works nearing completion.

This stretch is expected to deliver immediate benefits for both freight and passengers, improving connections between the Valencian ports, the Barcelona area and the French border.

Officials say these improvements will strengthen the wider Mediterranean arc, with eastern Spain set to become the first region to gain a fully operational segment of the corridor under the new planning.

But the government’s own map also reveals some striking gaps that have left the rest of Andalucia’s coast regions scratching their heads.

The omissions

For all the intricacy of the proposed map criss-crossing Spain with new high-speed train lines, Malaga does not feature at all, despite being a critical node and one of Spain’s busiest high-speed stations – not to mention the main transport hub for the Costa del Sol.

In fact, the entire Andalucian shoreline stretching 400km from Almeria to Algeciras, one of Spain’s busiest coastal regions, is left untouched by the so-called Mediterranean Corridor.

READ MORE: Why is the US sending an unknown number of B-52 heavy bombers to Spain?

This includes skipping out major population and tourism centres such as Marbella, Estepona, Fuengirola, Nerja and the wider Costa del Sol completely.

The Costa Tropical in Granada province is also absent, with no planned connection through Motril or the surrounding coastal towns.

Even La Linea and the Campo de Gibraltar, despite sitting next to one of Europe’s biggest ports in Algeciras, will remain without any dedicated Mediterranean Corridor alignment.

The other winners

On the other hand – and to little surprise for long-suffering Andalucians – Madrid and central regions of Spain will be richly served by a train network originally planned to benefit the Mediterranean regions.

Under the present design, the main long-distance freight route starting in Algeciras at the very end of the corridor swerves inland and heads towards Madrid instead of following the shoreline.

Trains travelling from the Port of Algeciras, or Almeria, will be funnelled into central Spain before rejoining the Mediterranean coast hundreds of kilometres further north.

This means goods moving between Andalucia, Valencia and Catalonia must pass through the capital, even when the most direct route runs along the coast.

This Madrid-centric layout has prompted strong criticism from Spain’s Mediterranean regions, who argue that the project no longer resembles the coastal corridor originally promised.

Business groups in Andalucia, Valencia and Catalonia have accused successive governments of shaping the route around the country’s traditional radial model, where major infrastructure feeds into Madrid rather than connecting peripheral regions to each other.

Campaigners argue that this approach undermines the goal of creating a fast, modern coastal link between the ports of Algeciras, Malaga, Almeria, Cartagena, Valencia and Barcelona.

They also warn that routing freight through central Spain adds distance, fuel costs and time compared with a true shoreline route.

El Corredor Madrileño

Supporters of a coastal route say it could increase freight handled by Mediterranean ports by 10 to 15% and reduce congestion on the A7 and AP7 motorways.

Environmental groups also question the decision to prioritise inland stretches, pointing out that sections through the interior require extensive tunnelling, including across parts of the Sierra Nevada, while a coastal line could make greater use of existing corridors.

The debate has a long political history, with critics highlighting earlier decisions that weakened or delayed the coastal option.

Critics say the Aznar government slowed progress in the early 2000s to avoid strengthening economic ties between Catalunya and Valencia amid fears of uniting separatists in the two regions.

They also mention the 2004–2005 Van Miert Report, which prioritised radial lines from Madrid after lobbying from Spain’s transport ministry, pushing the coastal corridor down the list.

Both PP and PSOE governments are accused of maintaining this centralised approach, even after the EU designated the Mediterranean Corridor as a priority route in 2011.

Business leaders say the pattern continues today, noting that the government has accelerated work on Madrid-linked extensions while the southern coastal stretch remains without a timetable or funded plan.

The absence of progress between Algeciras and Almeria has become a particular flashpoint, as one of Europe’s biggest ports continues to rely on slow mountain routes rather than a modern coastal link.

On social media, users have mocked the inland-heavy layout, describing the project as the ‘Corredor Madrileño’.

Campaigners warn that the corridor will never function as a true Mediterranean route unless the missing Algeciras–Malaga–Almeria section coastal stretch is finally built.

But with Madrid-centricism locked into Spain’s political system, they say only an appeal to Brussels may be strong enough to force them to complete the southern section.

Click here to read more Travel News from The Olive Press.

Don’t overlook the fact that Andalucía is one of, if not the only region not fully aligned with Sanchez and the Socialists. Punishment? Sure looks that way!

If the main reason for this project is to provide HGV’s alternatives to alleviate traffic on the roads,as is suggested in the article, then progress should be judged on whether this is being achieved. That won’t be possible until some sections are actually completed. Big projects like this always provide the politicians great sniping territory!

All I know is that over the last couple of years, here in Murcia, while there has been minimal disruption, it has been an education watching amazing engineering projects involving heightening bridges under which these new trains will pass, relocating complete stations, and new tracks being installed . Boys and their toys – sort of!