By Norbert Suchanek

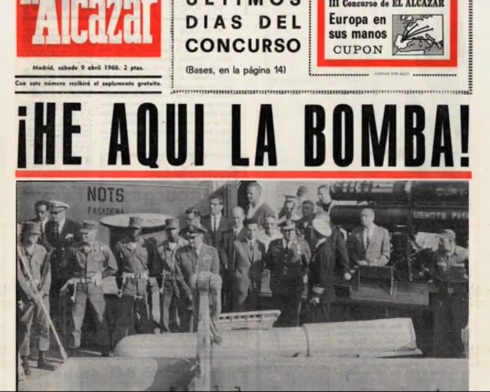

AT the height of the Cold War on January 17, 1966, two US military aircraft accidentally collided in the skies over Andalucia.

One of them, a B-52 bomber, was carrying four nuclear warheads.

As flaming debris fell from the sky, three of the bombs struck the ground near the village of Palomares, northwest of Almeria.

The impact caused the triggers in two of the hydrogen bombs to detonate. The nuclear material encased in the warheads did not ignite, but plutonium and uranium were dispersed into the air and soil, contaminating the area around Palomares for years.

A third bomb splashed into the sea off Almeria, and was only recovered 80 days later.

It was one of the worst nuclear disasters of the Cold War era.

Andalucian Jose Herrera Plaza was only a child when the accident unfolded. But it left a deep mark on him.

Today a film-maker, Herrera Plaza has been investigating the history of Palomares since 1986, writing several books and directing a documentary on the disaster.

Now, 60 years to the day since the two planes crashed over Palomares, journalist Norbert Suchanek interviewed Herrera Plaza to commemorate the tragedy.

Where were you in January 1966, when the hydrogen bombs fell from the sky?

I had just started school in Almería, about 90 kilometres from Palomares. Like most people in Andalucia, I had no idea that hydrogen bombs were flying over our heads.

When and why did you begin researching the Palomares accident and make it your main focus?

On January 13, 1986, I attended a meeting with residents of Palomares. It was three days before the 20th anniversary of the accident, and their claims for compensation for health damage were about to expire. I wanted to make a documentary about this little-known and almost unbelievable story, but at the time all sources for documentary films were classified. I waited 21 years, gathering all available documents, until I was finally able to complete the documentary “Operation Broken Arrow: The Palomares Nuclear Accident.”

What does ‘Operation Broken Arrow’ mean?

‘Broken Arrow’ is a US military code word. It refers to an accidental event involving nuclear weapons, such as an accidental or unexplained nuclear explosion, or the loss or theft of nuclear bombs.

How did the local authorities react? Were they aware of the plutonium threat?

The local authorities initially followed the protocol for an aviation accident. They only became aware several days later that nuclear weapons were involved and a large area had been contaminated.

How and when did the government in Madrid react?

Spanish authorities learned of the crash almost immediately, thanks to alerts sent through emergency channels by a Spanish Navy helicopter. The fact that the plane was carrying four hydrogen bombs was revealed later that same day by the US ambassador. However, both governments remained silent until, three days later, the media exposed the story to the public.

How was it possible for the media to report on this so quickly during the Franco dictatorship?

The Spanish-American journalist Andre del Amo, from United Press International, arrived in Palomares two days after the accident. He revealed that the accidents involved nuclear weapons and Geiger counters were being used in ground measurements. The following day, his report appeared in major media outlets worldwide. The dictatorship reacted in its usual way: it confiscated newspapers from newsstands and at the airports in Madrid and Barcelona as soon as international flights landed.

Anyway, residents of Palomares and the rest of Spain learned the truth because, to circumvent strict censorship, it was common practice to listen to Spanish-language shortwave broadcasts from Radio Paris, the BBC, and especially Radio España Independiente ‘La Pirenaica,’ the Communist Party of Spain’s station broadcasting from Bucharest, Romania.

What were the direct consequences of the shattered hydrogen bombs? Was there a risk of a nuclear explosion?

The two Mk-28 FI bombs each had 68 times the explosive power of the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. When they hit the ground in Palomares, the hydrogen bombs exploded because the conventional explosive charge in their triggers detonated. As a result, an area of 635 hectares was contaminated with fissile material: approximately 10 kilogrammes of plutonium-239 and -241, and slightly more than 10 kilogrammes of uranium-235 and -238.

While the risk of an accidental nuclear detonation was very low, it did exist. These hydrogen bombs were among the most technologically advanced in the US arsenal at the time, and their safety systems were generally effective – except for the conventional explosive, which was sensitive to shock and vibration. Because of this accident, and a similar one two years later in Thule, Greenland, the US military replaced that explosive with a shock- and fire-resistant version.

Was the local population warned about plutonium contamination and the consumption of potentially contaminated food, such as tomatoes?

Palomares residents were continually – and perversely – misinformed, both during the Franco dictatorship and later under democracy, for nearly fifty years.

They got a little help from one of the highest members of the Spanish nobility, the Duchess of Medina Sidonia, who informed locals about their situation and their rights. For this, the Franco dictatorship imprisoned her.

Are there data or estimates on how many people became ill or died as a result of plutonium or uranium contamination?

No, because a rigorous epidemiological study has never been allowed. When independent researchers have attempted such studies, they have encountered constant obstacles. At the same time, the official narrative maintained by both governments has insisted that plutonium has never caused any tumour diseases.

Palomares is an environmental sacrifice zone with significant health risks for its inhabitants. But it is not unique: around the world, invisible minorities continue to suffer invisible consequences.

Did the ‘nuclear accident’ affect the region’s emerging tourism industry?

In 1966, tourists visited other parts of Spain, but not this area. The province of Almeria was very poor and isolated, with poor transport connections. However, the dictatorship feared the accident might affect tourism in the rest of the country because of tabloid coverage, especially in the British press and parts of the Italian press.

The most sensational headlines came from a newspaper owned by a young Rupert Murdoch in Australia. It claimed that a nuclear detonation had occurred, that thousands of people were fleeing, and that the entire Spanish Mediterranean coast was contaminated. This prompted the highly publicized beach swim by the Spanish Minister of Information and the U.S. ambassador in Palomares.

The US military carried out a large-scale search and cleanup operation. How did the local population react?

The main priority of the massive military deployment was to comb through land and sea for the missing bomb. The land search lasted more than 45 days, and the sea search 80 days.

The second priority was to recover the black box and classified components of the B-52, such as radios and combat documents. The third was to collect more than 125 tons of wreckage from the bomber and the tanker and dump it into the Mediterranean off the coast of Palomares. Finally, only a symbolic decontamination was carried out, largely for international public opinion.

Some local residents likely suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Then a kind of collective paranoia took hold, intensified by contradictory statements from authorities in both countries. The population suddenly entered the atomic age, trying to understand a new word in their vocabulary: radioactivity.

Was the military able to remove all the plutonium from the region?

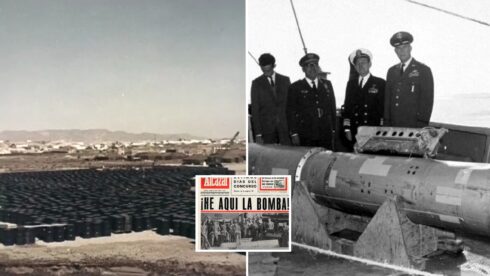

They removed only the plutonium they chose to remove. After long and unequal negotiations between the hegemonic power and the Franco dictatorship, an agreement was reached to decontaminate the area and return the plutonium to its country of origin. In practice, only 650 cubic meters of contaminated soil and 350 cubic meters of contaminated crops were removed.

This amounted to less than one percent of the plutonium – less than 100 grams – which was shipped to the US in 4,810 barrels. The most radioactive material was left behind. The remaining contaminated land was ploughed to bury most of the plutonium about 30 centimetres deep in agricultural fields. Forty years later, two secret pits were discovered containing 4,000 cubic meters of buried radioactive waste.

What was done with the contaminated material in the United States?

Two barrels were sent to Los Alamos National Laboratory for plant experiments. The remaining 4,808 barrels were shipped to the Savannah River Site of the US Atomic Energy Commission in Aiken, South Carolina, and buried six meters underground. This symbolic gesture was widely publicized.

Meanwhile, 99% of the plutonium and uranium remaining in Palomares was concealed from public view – especially from the residents and farmers working those radioactive lands.

The US Air Force and the Spanish government assured them that the area had been fully decontaminated and posed no danger. At the same time, the US Atomic Energy Commission and Spain’s Junta de Energia Nuclear took advantage of the situation to conduct a secret human experimentation program to study the uptake and retention of plutonium and uranium in people exposed to inhaled plutonium oxide aerosols. This programme, codenamed ‘Project Indalo,’ was carried out without the informed consent of the local population.

What is the situation in Palomares today? Are there still contaminated sites and radioactive hazards?

Despite official assurances from Spain and the United States, ploughing contaminated land in 1966 generated radioactive aerosols. For forty years, residents of Palomares were exposed to radionuclides. Only in 2006 were the first radiation protection measures implemented, restricting agricultural use, access, and transit in 40 hectares through fencing and warning signs.

Now, in 2026 – 60 years later – the area still awaits full decontamination by the central government in Madrid. It has never been treated as a priority, despite documented evidence that more than 210 residents showed symptoms of internal lung contamination. The true number of affected people remains unknown. Political elites live 525 kilometres away in Madrid.

Why was the B-52 bomber flying over southern Spain with atomic bombs in the first place?

Beginning on January 18, 1961, under Operation Chrome Dome, four to six strategic bombers flew over Spain every day, year-round, on outbound and return missions. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 42 bombers armed for massive destruction flew daily. These B-52s departed from the US East Coast, crossed Spanish airspace, approached southern Italy, and returned via Spain. Each carried four thermonuclear bombs.

For five years, until 1966, more than 17,000 bombers flew over Spain, refuelling 26,000 times. No other European country allowed such dangerous manoeuvres. Nearly 35,000 hydrogen bombs passed over Spanish territory. The accidents at Palomares and later at Thule, Greenland, occurred because probability was pushed to its limit.

How are you commemorating the 60th anniversary of the Palomares disaster?

I am planning a photo exhibition and a panel discussion at the Villaespesa Library in Almeria titled “Palomares – 60 Years of Government Failure.” I also expect to launch my new book at the end of January, called “The Year of the Bombs: Stories from Palomares.” It brings together testimonies from 27 Spaniards and Americans who were involuntarily involved in the accident. The book is written in the documentary narrative tradition, like Voices from Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexievich, to which it pays homage.

All of this is intended to prevent Palomares from being forgotten. The story of Palomares is not over. It is still being written.

Thank you.

Click here to read more La Cultura News from The Olive Press.

Interesting interview. Would be eager to read his book on Palomeres